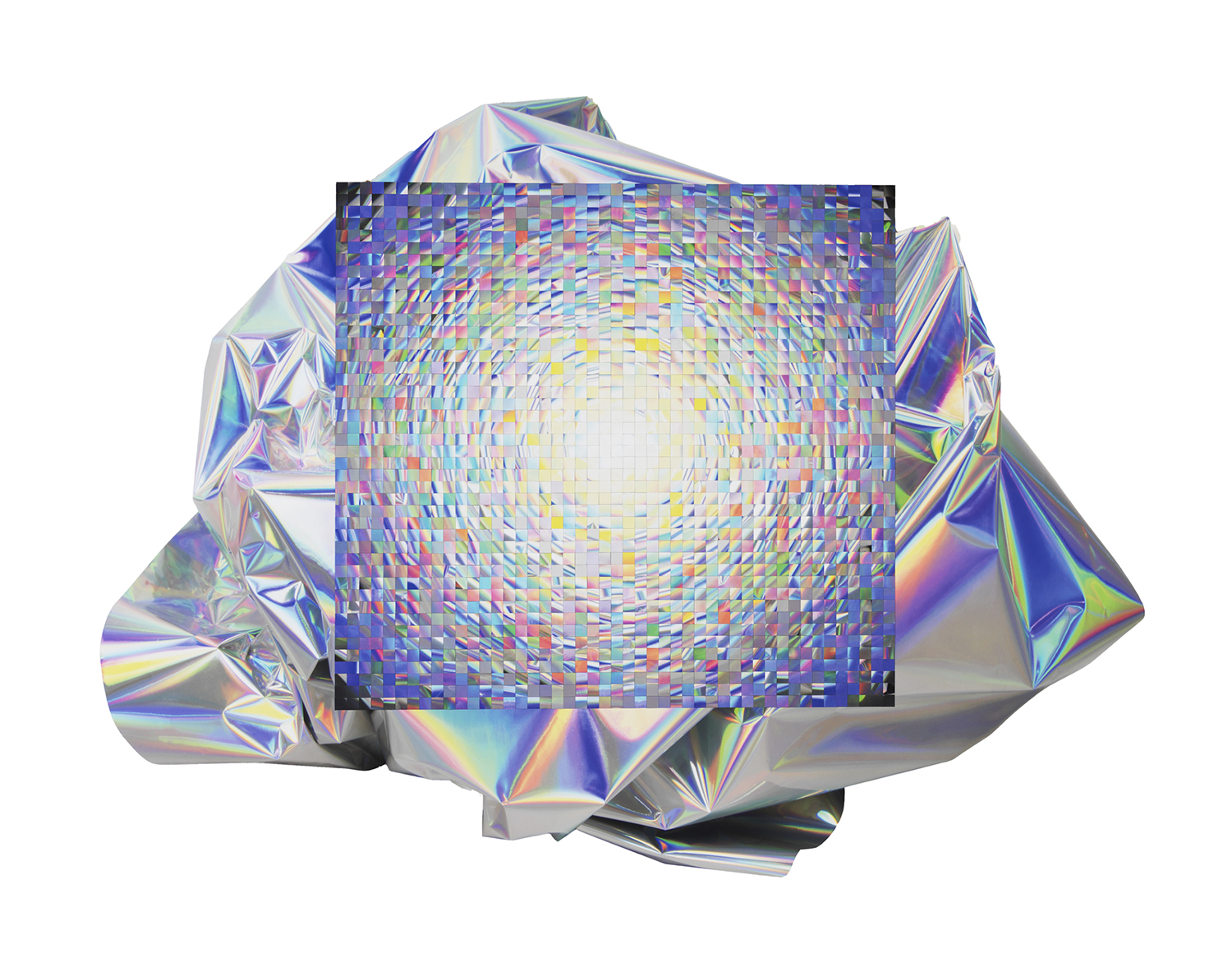

Deep Structure (Chromatic Dispersion A), 2017, Photograph and decollage, 50 x 66 in

It’s that leap of faith, jumping into the void, the deep end of the pool that you’re afraid of that you have to enter into in order to experience or know you can tread water.

Out back of an East Vancouver coffee shop, a tiny patio consisting of a picnic table and a bench basks in full sunlight. It’s the middle of a heat-wave in Vancouver and finding respite from the sun is top priority. At another time of day, this patio would offer that, but right now the sun is overhead. So, we move inside, tucked in a corner at a quaint and tiny table.

Ed Spence is one of those people with an easy smile, an attitude and presence that immediately make people comfortable. Somehow, our conversation opens with talk of the evolution of language and the use of shorthand. His grandmother was a stenographer for a time and I comment on the shorthand prevalent in today’s society, texting. Then, our conversation turns to art.

“I guess it’s a common cliché to say that we all start as artists and some of us stop,” he tells me. “And I just happened to not stop.”

“I got a lot of positive reinforcement at a young age,” Spence says, though he attributes it to a measurement of his copy-catting abilities. “I seemed to display a specific talent for rendering objects realistically or whatever happens to be an important artistic attribute for children to display. So I kept going and I found enjoyment in creatively reflecting on my experiences.”

Early on, I started playing with perspective, getting into these strange cubist and surrealist tendencies and seeing what would happen if I started distorting the natural characteristics of the world.

Spence tells me about growing up in the Thompson-Okanagan area of BC, where the winters are cold, the summers hot, and he spent a lot of time cutting up magazines. It’s a familiar activity, a stack of yellow-framed National Geographics and 1990s beauty mags ready to be repurposed for school projects and Saturday-afternoon arts and crafts. But Spence was taking it to another level.

“Early on, I started playing with perspective, getting into these strange cubist and surrealist tendencies and seeing what would happen if I started distorting the natural characteristics of the world. It allowed me to play God, in a way, which was a fun thing to do.”

What he now calls cubist and surrealist Spence may not have had the words for as a child, but the fundamentals of his future practice were already growing. “I would draw glasses on a politician or have them smoking a pipe or something, some sort of little doodles and culture jamming.” It’s easy to see the appeal for a child because, really, what he was doing was just having fun. As an adult, he still finds it fun.

“Instead of creating something from scratch, you’re mixing and collaging ideas in an intervention approach, where you’re being a parodist, where you’re poking fun at things and altering the meaning. There’s satire in it. That kind of questioning of the prescribed notions of what people present or perceive is in my work. There’s always a chance to change the meaning of something with subtle gestures or completely transform something or use something as a jumping off point for the work and incorporating what that previously was into the work. It started as non-art play, me having fun. And then I guess I started taking that idea a little more seriously.”

Instead of creating something from scratch, you’re mixing and collaging ideas, in an intervention approach, where you’re being a parodist, where you’re poking fun at things and altering the meaning. There’s satire in it.

Despite the art-filled home and encouragement from family, Spence wasn’t sure about art school or a career in visual arts right away. Following high school, his decision was actually between art school and trade school. “There was some lack of confidence early on in the fact that I could make [art] a realistic career.” Throughout high school he worked for his father, a contractor, so it was a promising alternative future.

Ultimately, he chose art school, attending Okanagan University College, which later became UBC Okanagan. But it was paid for with trades, as he worked his way through school by framing buildings and doing finishing carpentry.

One of Spence’s first collections was similar to his childhood doodles on magazines. “I was working with thrift store images: I would paint sea monsters attacking their ships and really silly images. One component of it was nautical themed with sea monsters attacking an installation.”

Aside from sounding like an excellent tattoo idea, that exhibit sparked future mashups and an interest in perception. Later, it manifested in his choice of process: cutting and retiling images. “One of the first pieces I did using that tiling mosaic was a thrift store image of flowers,” says Spence. “I cut it into a grid and reorganized it into strips so it emulated a VHS glitch. It was this break down of the mediation. It wasn’t actually the original used to display it, but referred to both a future and past time, freezing that moment and at the same time eluding to the image in flux.”

The root of my process was originally more of a meditation on digitization and changing media and changing modalities of representation. I’m interested in technology and perception, and the body and how we interface with the world.

That delivery format would become one of Spence’s signature art styles, but he uses it to explore other themes as well. Right now, he tells me, he’s thinking about transhumanism and the post-human condition. Technology, in ways like the VHS glitch, keeps making appearances in his new works, especially in exploring its relationship to humanity.

“I’ve been thinking about the potential to alter human perception and tap into other frequencies of understanding our world,” Spence explains. “The root of my process was originally more of a meditation on digitization and changing media and changing modalities of representation. I’m interested in technology and perception, and the body and how we interface with the world.”

How does he translate that to his art? Spence thought for a moment before trying to explain: “I was doing a meditation this morning and it crystallized in my head the imagery that I’m working with: this eminent light through a meditative act, breaking down the external perceived rational world and entering into this dream state where things are in flux and in movement.”

Imagine looking at an object, like a piece of fruit. When you shut your eyes and meditate on that object, you can still picture it in your head. The reality, that the fruit exists when you close your eyes, is assumed, but your experience of it within your own head may differ from what’s in front of you. That automatic breaking down and reassembling is what Spence is trying to convey through his mosaics.

For his Splash piece, Spence first photographed a holographic material called dichroic foil that breaks the light apart and reflects it back in a rainbow of hues. “It took weeks of playing with the photography to get the right kind of image,” says Spence, who had a distinct effect in mind. “I was developing that as a series, so that led to the seeds of maybe six images that I could Photoshop and then print out, cut apart, and then reorganize and stick together.”

I like to go in with a little bit of research on the material because I generally have some sort of goal I’m looking to achieve, whereas some people’s practices rely on finding out what happens when they mix two things together and have no idea what’s going to happen.

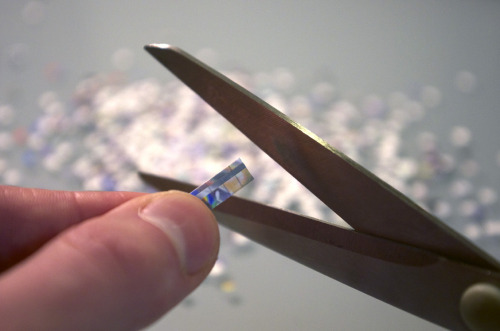

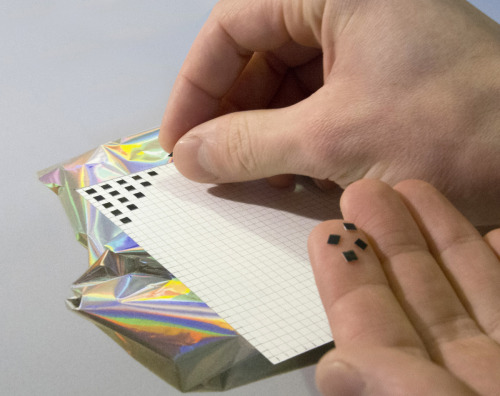

That beginning part of his creation process took some weeks, not to mention project development. The cutting, organizing, and tiling can take from days to weeks, depending on the scale and complexity of the image. “Sometimes the size doesn’t affect it as much as the size of the internal components so if I break the image up into 8,000 little squares, then it will be vastly different from breaking it into a grid of 6 x 6. And those are all laid out on a table in a spectrum of colours, in piles.”

Photographs of Spence’s process. Photo: Ed Spence/ Tumblr

While the mosaics make up a large part of Spence’s practice, he’s experimented with other media as well. Beyond painting, photography, and collage-making, Spence has dabbled with sculpture and film-making as well. During a two-month residency in Italy, he developed video accompaniment for a contemporary dance performance which was later shown at the Nah Dran performance series in Berlin. In partnership with Julianne Chapple, his wife and a choreographer, Spence has received Canada Council funding for their next project.

Their collective research on meditation and post-humanism has a physical outcome: “the body’s relationship to technology, abstraction, and abstract perception. There’s this kind of tech spiritualism thing that we’re investigating. She has a full-length piece coming up next year that we’re collaborating on sculptural elements, masks, and other paraphernalia, props, and objects to interact with, that will be very much related to my practice as well. We have a huge overlap in our work.”

Immersed in as many artistic media as Spence is, I ask him where he gets the confidence to pursue so many avenues. Since he didn’t study everything he does now while he was at school, Spence believes in calculated experimentation.

“It’s that leap of faith, jumping into the void, the deep end of the pool that you’re afraid of that you have to enter into in order to experience or know you can tread water. It really is just going in with an educated perspective, not being reckless when you’re entering into that, just coming in as informed and wise as you can, just so you’re not wasting too much time. Unless there’s no worry in the world. There’s freedom for that reckless play too. And some people do it differently. I like to go in with a little bit of research on the material because I generally have some sort of goal I’m looking to achieve, whereas some people’s practices rely on finding out what happens when they mix two things together and have no idea what’s going to happen. I find that happens inevitably during the process, even if you come in educated as to what you think is possible or what your goals are. There’s not one way to do it. Just do it.”

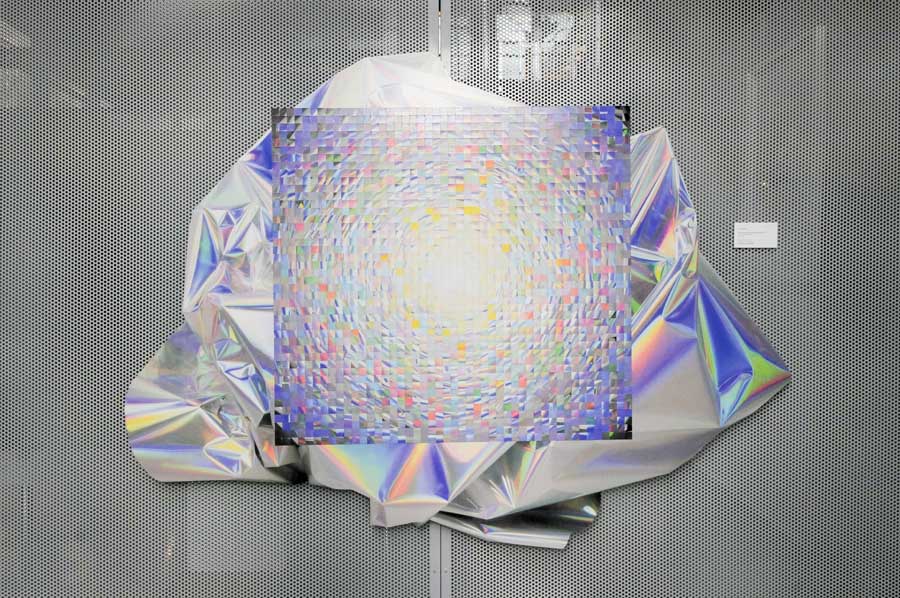

Gestalt Override on exhibit at the Pendulum Gallery Splash Preview Exhibition

MORE SPLASH ARTIST PROFILES

Hank Bull on Artist-Run Centres, Collaboration, and Boxes

Ian Wallace on Photography, Expo 86, and the Image in an Image

Jamie Evrard on Italy, Pretty Art, and the Circus

Bobbie Burgers on Building Stamina, Orchards, and Raising an Artistic Family

Lisa and Terrence Turner on Changing Careers, Making Mistakes, and Christmas Gifts

Andy Dixon on Punk Influence, New York City, and Becoming an Insider